Creating a good onboarding experience as a manager is tricky at the best of times. It’s even harder when you are forced to work from home against the backdrop of a global health crisis. It is harder to recognize the challenges of new hires and it’s harder for them to ramp up and integrate in the absence of ambient hallway chatter.

At the same time, it is possible and achievable. Looking back at my own onboarding journeys, I’ve learned a lot from the good, the bad and the ugly. Most learnings are transferable into distributed settings.

Let’s look at the bad ones first. Once, my new boss told me in our first meeting that he’s moving teams – I just relocated to the other side of the globe to work with him. That was also the job where I did not have a computer or a phone for the first week – particularly funny as I worked for a telco and had to read printed PowerPoint decks for the first week. Another time, I was put into “stealth mode” … without ever re-emerging. Or that time when I did not have a project to work on for the first two months – it was called “being on the beach” and it drove me up the walls.

But there were also the great experiences. When my new boss walked me through everything by himself – not just giving me the opportunity to ask questions, but guiding me through what he considered important. Or when I arrived at a desk with a brand-new machine including access to all relevant systems. Or the onboarding buddy, who took it as a matter of personal pride to make sure that I had a great start.

First impressions matter. Starting on the right foot and getting momentum is a great confidence booster for every new starter. At the same time, without guidance, new hires have to work twice as hard to learn what they need to be productive. When working from home, it takes a more deliberate effort to give new hires the necessary experiences and exposure for a solid start. Always remember that it is a bigger deal for them than it is for you. They will remember it, one way or another. Your job is to make sure those will be good memories.

Below are a few ideas that I collected over the years.

Get the basics right without fail

I once attended a conversation with Ben Roberts-Smith, a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award in the Australian Army. He shared his view on what separated elite units from other teams: They get the basics right – 100% of the time, without fail, no excuses.

Being exceptional is not about complex techniques. It is all about making sure that basic procedures were trained over and over so that everybody could rely on them.[footnote]Same with professional athletes. They are able to execute over and over and over throughout each season.[/footnote]

For onboarding, the basics are as follows:

- A welcome mail to your new hire before they start. Give them the opportunity to ask questions, help with logistics (when to be where, what to wear,[footnote]Dress code can be quite anxiety inducing and nobody wants to take a gamble for their first day in the office[/footnote] …) and effectively transition them from the recruiting to the onboarding stage.

- Basic equipment is ready before day one. Desk, computer, displays, chair, logins and everything else that is necessary for them to get started. In work-from-home settings, ship the equipment well ahead of time. Also let them know if they have a company allowance to spend on a home office setup. Every person who starts a new job is excited to get going. Make sure they can.

- A team member welcomes the new starter. Traditionally that would have been in the lobby. These days it’s a phone or video call first thing in the morning. Welcome them to the team, guide them through their initial steps and answer first questions. This is just an intro. Go easy on them and don’t overwhelm them just yet.

- Welcome mail to the team. Include a photo[footnote]If the new starter is fine with it.[/footnote] and a short blurb that covers their background, something light-hearted and what they will be working on.

That’s it: welcome email to the new hire, equipment ready, greeter at the door and a welcome email to the team. For every new starter, every time, on their first day, with a smile.

Invest in a starter document

Standard checklists for the first day, week and month are a good starting point. Take it to the next level by creating a custom starter document for each candidate. The purpose is to help them hit the ground running. It also signals that you put thought into that person’s experience. Topics that the starter document covers are:

- What success looks like: Write down your expectations for the first 30 days. Outline what you expect the new starter to be able to do, have completed or responsibilities they have taken over. Don’t gloss over it, but put thought into it and write it down. In remote settings skew those goals more towards building relationships. Google’s study about successful teams revealed that a key driver of success is psychological safety. Team members should feel safe to take risks and be vulnerable in front of others. You can only get there if you know the people and the culture of the place. That’s more difficult in distributed settings. Set checkpoints around building relationships, getting to know people and learning how the organization works.

- People to engage with: A list of people to have conversations with and suggested topics to talk about. Not everybody is a social butterfly and born networker. That’s why it’s important to have suggested topics to talk about. It can make the difference between an awkward chat and the start of a great collaboration.

- Critical documents to familiarize with: These can be wikis, strategy memos, notes from the last code review, etc. Any artifacts that show what is important for the team and how the team operates.

- Mentoring: To set the new team member up for long-term success, encourage establishing a relationship with somebody more senior outside of the team. While the best mentoring relationships evolve organically, it helps to kick-start the process and identify a potential mentor. Ideally, they are 2-3 years ahead of them. If the gap gets bigger, most people develop a rose-colored nostalgia filter and become less helpful (“We were hungry, broke, and miserable. And we liked it fine that way!”).

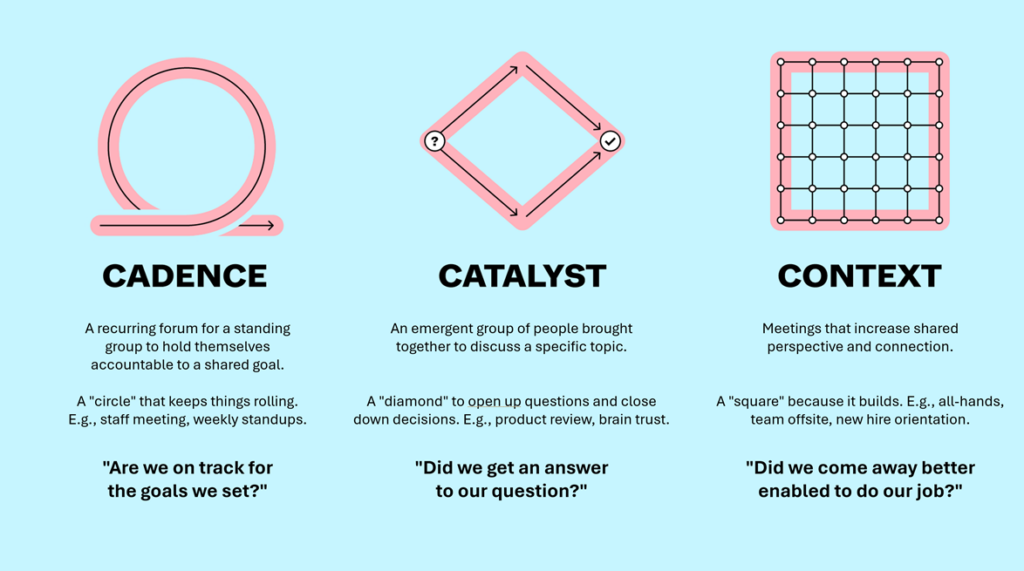

- Core meetings: What are the regular meetings that this person should attend. Those meetings are a good opportunity to experience team culture, get context and get exposure to other team members. Be mindful of invites in work-from-home arrangements. In the absence of ambient hallway chat, a new hire will never find out about a meeting if you don’t explicitly let them know.

A starter document takes time to compile. It is an investment and that pays dividends in terms of getting your new team member started on the right foot and building meaningful relationships right from the start.

Assign a starter project

A big driver of job satisfaction in the initial few weeks is the first project that a new hire works on. Set them up for success. It should provide the right mix of challenge, learning, contribution and opportunity to shine. Having a starter project can be the difference between second guessing your job decision and creating a feeling of belonging and emotional safety.

It should be the exception that you don’t have a starter project. In those rare cases, explain that you are still identifying a project and that you want to set them up for success rather than keeping them busy. For the first few days that can be OK. But after a week, there should be a project that they can dig into.

Let them own the onboarding document

The onboarding document is a team-specific collection of “all the things I wish I had known when I started here”. Below are some ideas for inspiration:

- Checklists for the first few days

- Link to professional development framework, career paths, expectations for each level, …

- Highlight projects: artifacts from the best projects of the last 2-3 years.

- Common data resources: how to access tools, industry data, telemetry, repos, …

- Helpful links in the company intranet. The lunch menu always makes this list.

- Link to the company org chart.

- Printer instructions and how to fix common problems with your machine and how to contact the help desk.

- Most commonly used acronyms.

- How to get to the office, where to register the car for parking, …

- Company discounts: most companies have deals with local businesses. Either list them here or link to them.

The onboarding document should cover all those questions that one might be embarrassed to ask, but that everyone has.[footnote]Basecamp has published their Employee Handbook, which is a good source for inspiration. Clef has done the same. [/footnote]

Starting an onboarding document is always hard. Start small and have the team collectively create a first draft, the 80% version. Then ask each new starter to be the custodian of the onboarding document for the first 30 days. Let them fix links that went out of date, add the stuff they found useful and clean up the structure when things got out of hand. Ask them to present their changes at a team meeting. That way, everyone benefits from their changes. Over time, that document will get better and better.

Check-in often

Throughout onboarding, stay in touch with your new team member. Now that we are all working remotely, this is critical. They haven’t built their network yet and might feel lost. Include them as much as possible to avoid unpleasant surprises.

Be available and respond in a timely manner. In addition, put formal check-ins into the calendar after the first week, the first month, the first quarter and the first half year. Schedule them well in advance, listen carefully and answer their questions.

I recommend assuming some of the responsibility for new hires to hit their 30-day goals. It’s much harder for them in remote settings, especially if the company is not a traditional distributed company. Pay attention and do your part (e.g. inviting them into meetings, making sure they get exposure, warming up contacts, …). Otherwise your new team members will have to work that much harder.

Last, but not least, encourage your new team member to come up with things that should be fixed at the 30-day check-in. After a while all of us develop blind spots with the status quo. Having fresh eyes to point out things that are broken is an opportunity to reverse-engineer a better onboarding process.

The 180-day check in might seem odd, since the new team member no longer feels “new” and is fully immersed in the team. Reflecting on the first few days with a bit of distance means that people are no longer starry-eyed and bushy-tailed. I had quite a few people tell me “When I started, I thought it was my fault that [X] didn’t work, but now I know that this part is broken and needs to be fixed.” [X] might be a system, a process or the attitude of a fellow teammate, who forgot how challenging the first few days on a team are.

Last words

So, there you have it:

- Get the basics right without fail

- Invest in a starter document

- Assign a starter project

- Let them own the onboarding document

- Check in often

First impressions matter and a good onboarding experience makes the difference between a highly engaged, confident and productive team member and an unnerved employee that feels disconnected. They need to work twice as hard to recover from a failed start. While the bar is raised in the middle of a global health crisis, a good onboarding experience is still achievable. Companies like Automattic and Basecamp who have been working with distributed teams by default show the way.

Always remember that this is a much bigger deal for them than it is for you. They will remember it for a long time.

Photo by Braden Collum on Unsplash